Photo credit: ILO / Marcel Crozet

To better understand working conditions in a labour market and help better inform interventions and measure progress towards decent work, Rapid Asia, in a recent study for UNOPS, examined the prevalence and magnitude of wage theft in Myanmar. But what is wage theft, and how can it be calculated?

The following story is a good example of wage theft. For nearly two months, a betel nut farmer in southern Myanmar didn’t receive any wages. Despite being legally protected under several of her country’s labour laws, she was expected to work overtime and still received below minimum wage. If she complained, she was told she could lose her job.

“My employer is always late in paying my salary and does not give me the full amount he owes me. He said he would pay me once every ten days, but he has not paid me for more than two months. I don’t have any money saved now.”

The denial of wages owed to workers, also known as “wage theft,” is common among low-skilled workers, particularly in the informal economy. There is no agreed definition of wage theft, and it can come in different forms of labour rights abuse. Examples of wage theft include withholding wages, not paying the legal minimum wage, not paying for overtime, not providing social protection benefits, making illegal wage deductions or misclassifying work to avoid paying higher wages or benefits.

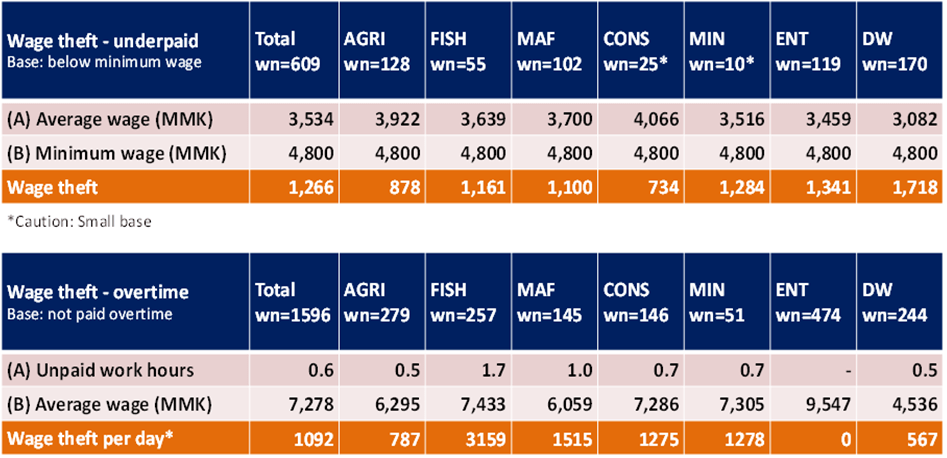

In the study conducted by Rapid Asia in Myanmar, over 2400 workers were interviewed in the fishing, manufacturing, construction, mining, agricultural, domestic work, and hospitality sectors. Two of the more common examples of wage theft were examined – paying below the legal minimum wage and overtime pay (Table 1 below). The study found that the average wage was below the minimum wage in all sectors, and wage theft was on average MMK 1,266 per day (approximately $0.60). That represents an underpayment of 26 per cent. When it came to overtime payment, the average wage theft was MMK 1,092. Whilst wage theft occurred across all sectors, and it was more prevalent in fishing, manufacturing, mining, and domestic work.

Table 1 Amount lost to wage theft through underpaying and lack of overtime by sector

The case of Myanmar provides a stark picture of the challenges wage theft pose globally and how many workers in both the informal and formal sectors may be denied income illegally. The problem has increased with the spread of COVID-19, especially amongst migrants workers who often are disproportionately affected by the pandemic.

Despite the existence of legal protections and laws, workers often have no choice but to accept the abuses by their employers. Lack of law enforcement and complaint mechanisms in many countries means employers face minimum risks of repercussions. Insufficient awareness of their rights further adds to workers’ inability to secure protection. Finally, disagreement amongst policymakers and employers as to whether or not fair labour standards, such as minimum wage and overtime pay, should apply to informal sectors leaves many workers without a living wage.

Based on the study findings, the following recommendations help to address wage theft:

- Strengthen legal frameworks for wage protection to ensure better prevention and enforcement measures are in place.

- Increase access to remedies for wage-related abuses in the form of recovery of unpaid wages and financial compensation.

- Develop standard employment contracts for sectors with high levels of abuse.

- Ensure that workers have access to justice for labour rights violations.

As world leaders try to revitalize their economies amid the global pandemic, they must avoid doing so at the expense of workers who will help drive the recovery effort. Just as mass vaccinations should be pursued to help protect the general population, fair labour standards should be strengthened to protect those most vulnerable and unable to work from home. Download the full report here.

If you found this article useful, please remember to ‘Like’ and share on social media, and hit the ‘Follow’ button never to miss an article.

About the authors: Daniel Lindgren is the Founder of Rapid Asia Co., Ltd., a social research and consulting firm based in Bangkok specializing in evaluations for programs, projects, social marketing campaigns and other social development initiatives. David Young is an independent consultant working with Rapid Asia as a member of their expert panel of consultants. Learn more about our work at www.rapid-asia.com