A study by Rapid Asia, conducted on behalf of ILO Ethiopia in 2017, estimated that 72 percent of returned migrants could be regarded as forced labour. Most of the returned migrants had entered the Middle East using irregular channels, in many cases going through transit countries, placing them at significant risk of exploitation. The study found that irregular channels, especially when broker fees are involved, and lack of basic pre-migration services, impact significantly on forced labour outcomes. See also the full report

The ILO Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No. 29) defines forced labour as “all work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily”. In the ILO framework, indicators for measuring forced labour are classified into indicators of involuntariness and indicators of penalty (or menace of penalty). Harassment and humiliation, constant surveillance, restriction of movement, withholding wages and physical violence were different forms of penalties found to be most common in the Middle East. A forced labor case is confirmed when indicators of involuntariness and penalty are both active, and this was true for 72 percent of the returned migrants in Ethiopia.

Forced labour can take place at any time in the migration process, and for returned migrants in Ethiopia, 49 percent experienced unfree recruitment, meaning they were either forced to work for an employer against their will or were deceived into taking a job the worker would not have accepted had he or she been aware of the true working conditions. Some 60 percent also experienced work and life under duress, which includes adverse working or living situations imposed on the worker.

Women domestic workers are often required to be available for work at any time and are often required to work for several family members. Women migrant workers, worked on average 16 hours per day and 82 percent worked seven days per week. Overall, 44 percent also experienced impossibility of leaving their employer, a form of limitation on freedom and an essential ingredient of forced labour. This is particularly relevant in the Middle East where the kafala system is still followed in many countries. Under the kafala system, the employer acts as an in-country sponsor and a worker’s visa is tied to their sponsor. Hence, the worker cannot leave without written permission from the employer. Since the vast majority of migrants are female domestic workers, this places them at significant risk of not being allowed to leave at the end of the work contract.

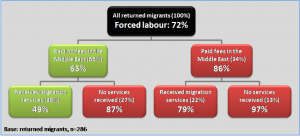

Reducing forced labour is a key priority. To better understand what conditions potentially drive forced labor, decision tree analysis was done using the Chi-square Automatic Interaction Detector (CHAID) method. A number of dichotomous variables from the study were included to build a decision tree and determine which conditions best merge to explain forced labour outcomes. The conditions found to drive forced labour are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Drivers of forced labour

Two conditions were found to have the strongest impact on forced labor outcomes: whether or not returned migrants paid a recruitment fee in the Middle East, and whether or not they received pre-migration services. Paying recruitment fees in the Middle East is strongly associated with irregular migration channels and transiting through high risk countries like Yemen, Djibouti, and Somalia. It also suggests smugglers were involved. When such fees were paid, forced labour cases increased to 86 percent, as opposed to 65 percent when not paid. The second condition relates to pre-migration services including skills training and pre-departure orientation. When migrants received such services in combination with migration channels that don’t require fees in the Middle East, forced labour outcomes decreased to 49 percent. When the opposite was true, becoming a forced labour case was almost guaranteed at 97 percent.

Considering that migration services in Ethiopia remain underdeveloped, there is significant potential to further reduce forced labour cases by providing basic but relevant skills training and pre-departure orientation, while at the same time promoting the use of regular migration channels. This approach is likely to apply to other countries as well and should be a good starting point for any program that strives to achieve safe migration.

If you found this article useful, please remember to ‘Like’ and share on social media, and/or hit the ‘Follow’ button to never miss an article. The full report “Baseline Survey: Improved Labour Migration Governance to Protect Migrant Workers and Combat Irregular Migration in Ethiopia Project” can be accessed here.

About the Author: Daniel Lindgren is the Founder of Rapid Asia Co., Ltd., a management consultancy firm based in Bangkok that specializes in evaluations for programs, projects, social marketing campaigns and other social development initiatives.

Credit Photo: TesfaNews, Ethiopian migrant domestic workers mark International Workers’ Day in Beirut by demonstrating for basic rights